The effects of using should in and out of intimate relationships

- What is a panopticon?

- How is it that couples become trapped in the panopticon of should in their intimate relationship?

- What happens to your friendships, your intimate partnerships, and your relationship to society when should comes into the picture?

- What happens when your intimate partner should(s) on you?

- What causes and what happens when you should on yourself?

When your intimate partner should(s) on you, they are laying their expectation and judgment of how you are supposed to think, feel, or behave, in effect trapping you into a place of compliance or rebellion. Compliance with their should allows you to stay in their good graces, perhaps at the expense of your authentic true self. Rebellion against their should creates discord, risking the loving connection you have been enjoying.

Thus, either decision is fraught with peril.

How is this happening? How many of us learned to use should as a method of controlling each other? How do we become prisoners of our own self-shoulding?

We have found that the word should, carries an extraordinary weight, influencing our thoughts, actions, and relationships in ways that can either uplift or suffocate us. It has the power to inspire positive changes and motivate personal growth; However, it can also entangle us in unrealistic expectations that tear away at our self-worth. When we consider the nuances of should through the lens of the Panopticon—a concept introduced by the French philosopher Michael Foucault (1926- 1984), we see how its impact echoes throughout our lives and relationships, particularly within the context of trauma.

Foucault’s concept of the Panopticon (Mason, 2024) stemmed from his notion of a kind of prison designed in or around the seventeenth century in Europe. In that prison stood a central observation tower, which allowed guards to see all of the inmates while themselves remaining unseen. This architectural structure was called a Panopticon and created a sense of perpetual surveillance, requiring inmates to monitor their own behavior out of fear of punishment. This concept of the panopticon effectively demonstrates how societal norms can impose a similar pressure to conform, making us feel that we are constantly being watched even when alone.

For many individuals who have experienced trauma, the word should can transform into a cruel manager, its own panopticon, leading to perfectionism and self-doubt. When trauma colors our perspective, we may create rigid and harsh self-expectations, which cause us to monitor our thoughts, feelings, and behaviors constantly. For example, someone who has suffered emotional neglect might think, “I should be stronger” or “I should be able to manage my feelings better.” This internal dialogue does not serve as a motivator. Rather, it reinforces feelings of inadequacy and failure and is a constant form of self-monitoring punishment. The pressure mounts to meet impossible standards and the result is often a debilitating cycle of self-criticism. The individual may find themselves perched on the brink of anxiety and despair, further exacerbating their emotional wounds.

Within romantic relationships, one partner’s expectation that the other should fit a certain mold can intensify the effects of trauma. Imagine a scenario where one partner, struggling with their own trauma, constantly projects their should(s) onto the other, saying things like, “You should always know what I need,” or “You should never let me down,” or state something more vaguely such as “You should never engage in that kind of language, or behavior.” This dynamic effectively places their partner in an untenable position. The receiving partner may begin to feel as if they are walking on eggshells, always striving to fulfill unspoken demands while suppressing their own thoughts and emotions. This imbalance can lead to feelings of resentment, isolation, and, eventually, emotional detachment.

The all-consuming nature of these should(s) can create turmoil within oneself and between partners. Those caught in this cycle may struggle to communicate openly and freely as they are mindful of their need to conform to their partner’s expectations. The fear of judgment can stifle authentic self-expression, making it difficult to voice one’s feelings or needs. As partners withdraw into themselves, the warmth of emotional intimacy begins to evaporate. They lose touch, not only with each other but also with their authentic true selves.

How trauma and the usage of the word should are related?

We have found over our many decades of research and clinical experience that most people, by the time they reach adulthood, have experienced some form of trauma, whether it is large ‘T’, small ‘t’, or a combination thereof. Trauma, by its nature, reveals how vulnerable we all are, and the experience of trauma often leaves individuals fearing and/or deciding that they never wish to be vulnerable again. This belief is in direct contradiction to what needs to occur in the healing of trauma. The protective walls that trauma survivors have built also keep them from being able to connect deeply with others, as well as with their authentic true selves. Helping individuals build the resilience necessary to be vulnerable is, therefore, one of the most vital tasks in therapy, especially with trauma survivors.

How do we learn shoulding on ourselves and/or on each other?

The usage of should often comes up with trauma survivors, and in a way, these two concepts can be seen as first cousins to each other. When individuals experience trauma, they may develop rigid notions of what they think they ought to feel, do, or achieve—a framework that often does not align with their lived experience. This internalized pressure to conform to an arbitrary standard can lead to a surge of negative emotions. As a result, individuals find themselves struggling with stress, guilt, or fear because the weight of these should(s) can create a constant state of inner conflict. These negative mental states can be particularly disruptive in couples, where differing expectations can exacerbate misunderstandings and create a growing gap between partners.

The following are some examples of what we have heard from our clients related to the word should, all of which are based on projection. As a reminder, projection is based on the belief that ‘only I’ know the right way of thinking, feeling, or behaving and that the other person is wrong for doing it their way:

‘You should have known better.’

Does this statement build up your partner or tear them down?

Within the dynamic of unhealthy relationships, the word should is often a projection as a result of earlier trauma(s) and the associated ego defense mechanism(s) that the person uses to cope. The ego always wants to be right and gets a charge out of controlling and making the other person wrong. Unfortunately, when this occurs, the other person’s ego also wishes to be right, and this often leads to disagreement and arguments, creating more distance between the two.

‘You should be more supportive’

If either you or your partner use this statement, how does it feel?

Do you realize it might make you and /or your partner feel guilty or inadequate instead of encouraged?

‘You should know how to make me happy.’

Does this statement create pressure or resentment in your relationship?

‘You should have remembered our anniversary.’

Is this a way that places blame on your partner, and how might your partner respond to that? What does this do to your intimate connection?

‘You should manage your emotions better.’

Does this make your partner feel supported or judged? Do you think they feel understood?

‘You should be grateful for what I do for you.’

Will your partner feel grateful, or will they feel a sense of obligation? Does this bring you closer or move the two of you further away?

How do couples become trapped in the panopticon of should in their intimate relationship?

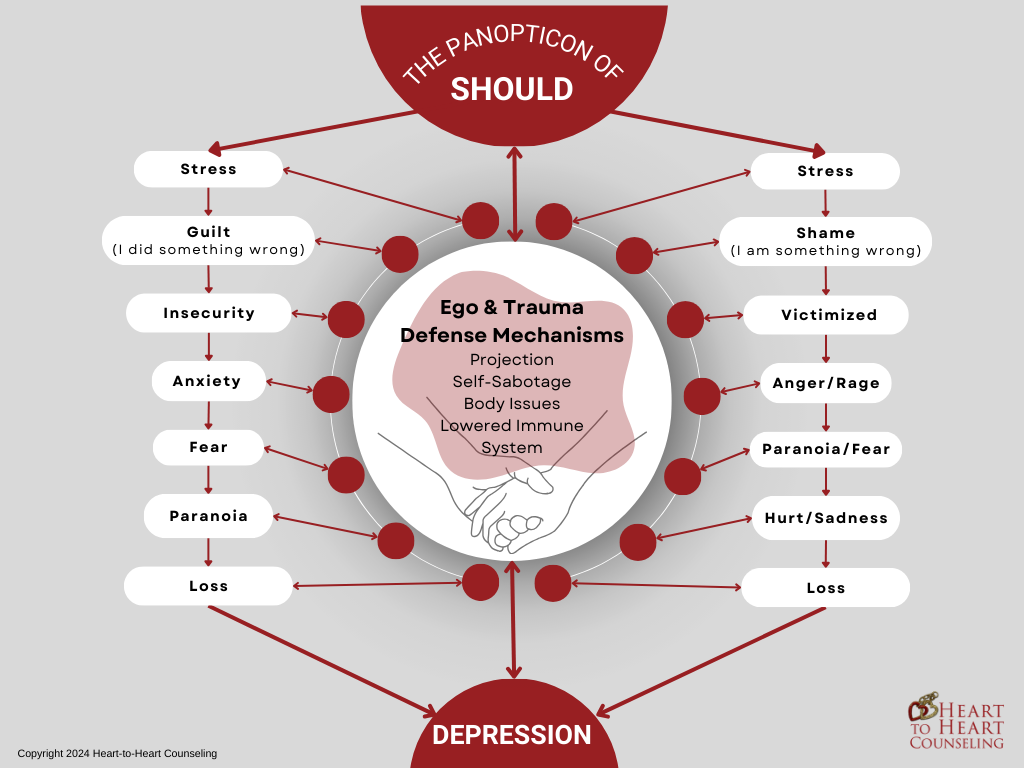

This question is meant to provoke thought and discussion about language’s impact on relationship dynamics and emotional intimacy, particularly the word should. The experience of trauma always makes us feel unsafe. Feeling and being safe are the ego’s main functions, so to achieve this, the ego creates strict rules that it believes must be followed. These rules get expressed as should(s), become internalized, and affect how we feel about ourselves. They also get projected onto others, usually someone close to us. In effect, these internalized rules cause us to should on ourselves, which creates feelings of guilt and shame. These feelings of guilt and shame get expressed in one, two, or three of three ways. One is that they get projected onto another person, as we just stated. The second way is that they come out through self-sabotage behavior(s), i.e., forgetting where we placed our keys (minor) or using addictions to ‘forget’ our troubles (major). The third way is through the body, where we store negative emotions, which can be expressed through headaches, stomach problems, digestive issues, etc. There is currently much research being done on how negative emotions can lower the immune system, creating ways for opportunistic infections and diseases to occur (Cousins 1979).

Please see the graphic below for further details on The Panopticon of Should and how it impacts our lives.

Language plays a pivotal role in influencing our emotional states and behavioral responses. Using the word should can be particularly damaging, invoking feelings of guilt and shame that engage the brain’s fear pathways and impair our ability to think creatively or problem-solve. Neuroscientific research indicates that punitive language activates certain brain areas, leading to a fear response that can inhibit personal development (Siegel 1999). Conversely, utilizing positive language and rewards activates the brain’s pleasure centers, enhancing motivation and fostering personal growth. This understanding emphasizes the critical need for shifting our communication styles whether in therapy, parenting, or other relationships—to favor positive reinforcement over punitive language. For example, in one family, when ten-year-old John came home with four Cs and two Bs, his mother said: “I am very disappointed in you. You should try harder to get good grades.” In another family, eleven-year-old Barbie came home with the same four Cs and two Bs. Her mother said: “I am so proud of you for getting the two Bs in those subjects. How do you feel about your report card?”

In many families, children grow up amidst a disproportionate amount of criticism compared to encouragement, leading to internalized feelings of unworthiness. Once a person has experienced trauma, feelings of guilt (The belief that one has behaved wrongly) can easily emerge from the relentless internal dialogue that accompanies the word should. A person may say to themselves that they should be over it by now or that they should be happier, more productive, or better adjusted. Using this line of thinking not only increases one’s sense of inadequacy but also creates a negative cycle of self-blame (a form of self-sabotaging behavior) and shame. It can become extremely difficult or nearly impossible to engage with one’s emotions authentically when weighed down by the idea of what one should be feeling. Whenever that expectation surfaces, it reinforces the negative belief of failing to meet these arbitrary standards, which can further fuel negative feelings and hinder the healing process.

In the same vein, the belief that should is correct can lead to an underlying current of paranoia and insecurity. One may find oneself constantly worrying about how others perceive them. One may obsess over how well they are meeting the expectations that have been imposed upon them, whether by parents, society, relationships, or their own internalized beliefs. This perception creates a panoptical effect—where they believe they are perpetually under scrutiny, which raises their anxiety levels and casts a shadow over all their interactions. It’s as though a silent observer is always watching, judging, and comparing, looking for what one is doing incorrectly. This keeps them from being authentic in their relationships and creates an environment of mistrust, making connections feel more like a performance than genuine intimacy.

The emotional toll that such a mindset takes can also give rise to profound sadness, anger, and rage. One might start to express frustrations through outbursts or withdrawal, feeling trapped between the emotional burdens of their trauma and the responsibilities of meeting societal or self-imposed standards. Anger may emerge as a secondary emotion, masking deeper feelings of vulnerability and sadness. This anger often isn’t just directed outward; it can also turn inward, leading to a cycle of self-destructive behaviors that further alienates one from both themselves and their partner. When one fails to express their emotions, they often fester beneath the surface, awaiting an outlet that may not always be healthy or constructive.

Shame (the belief that one is innately flawed) creates a feeling of victimization and is often intertwined with the constant pressure to meet expectations. One might feel ashamed not only of what has happened to them but also of how they are coping with it. The burden of should often leads to a downward spiral of fear and anxiety, stating over and over that how he or she is experiencing themself is not enough. This shame can act as a significant barrier to being vulnerable, preventing an individual from seeking the support that is desperately needed from partners or friends. Unfortunately, the more an individual is stuck in shame, the more isolated they feel, which compounds their feelings of sadness and hopelessness.

The following are further examples of what we frequently hear in couples’ therapy from our clients on how using the word should in their Intimate relationships is, at best, not useful and at worst, harmful:

Invalidating feelings: Saying “…You should just get over it…” can make an individual feel that their emotions are unworthy or trivial, leading to feelings of isolation and frustration instead of understanding.

Another often-used response to “should” is that “no one understands me or cares about what I do or how much I do for the family.”

Eroding trust: Using “…You should have told me…” when a partner brings up something later can create an atmosphere of distrust, blaming the partner for not being open, and may discourage them from sharing in the future, the exact opposite of what is desired.

Creating division: Statements like “…You should spend more time with my family…” impose expectations that may clash with individual priorities or comfort levels, leading to resentment and a sense of obligation rather than a genuine desire to engage.

Here are some examples of how taking responsibility for one’s feelings provides a better outcome for both partners:

Promoting emotional awareness: Instead of “…You should just get over it…” a partner might say, “…I feel concerned and unsure about how to support you. How can I help you through this…?” This tends to create a supportive environment where feelings can be discussed openly.

Encouraging personal growth: Replacing “…You should be able to handle this by now…” with “…I feel worried about how you’re coping, and I’m here if you want to talk about it…” invites partnership and shows concern without setting unrealistic expectations.

Creating transparency: Instead of “…You should have told me…” a partner could express, “…I felt hurt when I found out later; I want us to be open with each other…” which encourages honesty and addresses the underlying fear without assigning blame.

Encouraging acceptance: Changing “You should dress nicer when we go out” to “I love it when you wear that outfit because it makes you look confident. What do you think?” reinforces appreciation for the partner’s individuality and promotes open discussion about preferences.

Cultivating vulnerability: Replacing “You should handle your problems better” with “I feel concerned when I see you struggling. I want to support you; what do you need from me?” allows for a safe space for vulnerability and emotional sharing.

Freeing ourselves from the panopticon of should: A journey towards authentic intimacy

Our experiences working with both individuals and couples suggest that by moving away from the accusatory and prescriptive nature of should, partners can engage in more productive, compassionate conversations that create intimacy, understanding, and mutual support. By focusing on personal feelings and constructive communication, partners can cultivate a more supportive and understanding relationship that honors both individuals’ needs and perspectives.

To free ourselves from the panopticon of should—where expectations dictated by past traumas and societal norms create our thoughts, feelings, and behaviors, we must cultivate emotional intimacy through openness and vulnerability. The pervasive feelings associated with should restrict our relationships by promoting defensiveness and impeding genuine connections.

At the heart of this liberation is the understanding that secrets stem from fear. When we keep secrets from our partners, we limit our capacity for intimacy. Fear inhibits our sense of safety, and safety is the mainstay of emotional intimacy. When we are able to share our vulnerabilities and confront our fears openly, it creates emotional transparency, allowing for deeper intimacy and understanding in our relationships.

Our MDRT model of psychotherapy and should

Within our MDRT model of psychotherapy, we observe how language can either build or damage relationships. The use of should often creates profound stress that leads to defensiveness, blame, guilt, and shame, acting as barriers to effective communication. To dismantle these barriers, we encourage couples to take responsibility for their feelings and express themselves in ways that invite dialogue rather than defensiveness. By reframing accusatory should statements into expressions of personal feelings, couples can foster a more open and honest dialogue that promotes intimacy and emotional growth.

The transformative power of this approach is evident in many of our clients. By owning their feelings, wants, and desires instead of projecting them onto their partners, individuals break free from the cycle of perfectionism and the constraints of toxic should(s). In creating a space where emotions can be articulated without judgment, couples facilitate healing and connection.

Despite these opportunities for growth, many individuals face resistance when it comes to emotional vulnerability. Many mistakenly equate vulnerability with weakness, often feeling shame in expressing their authentic selves. Our MDRT model assists couples in engaging in compassionate dialogue, enabling them to dismantle rigid, often subconscious expectations that maintain the panopticon of should. Through this process, couples learn to cultivate trust, acceptance, and mutual respect, exploring their true selves without fear of judgment.

Making a judgment is different than giving an opinion. An opinion, when stated as such, allows the other person the freedom to evaluate whether they agree, partially agree, partially disagree, or disagree, opening up the door for further conversation. The nature of judgment is different since the person literally puts themselves in the position of the judge (as in a court of law), and as we know if you disagree with a judge, you get in big trouble. Also, as we know, one cannot disobey the judge. In relationships, when one is judgmental, they express themselves both with certainty and put themselves in a position, stating, ‘I know better than you.’ Whether that is true or not, the recipient of the judgment will usually feel put down, often get defensive, and the shoulding begins.

As partners learn the negative impact of the judgment, they can put out their thoughts and feelings authentically without attempting to make the other person wrong. Instead, they can co-create stronger and more resilient relationships rooted in empathy, where both individuals celebrate imperfections and nurture each other’s emotional needs. We have witnessed couples reach a stage where they can humorously discuss their vulnerabilities, recognizing that these aspects of humanity deepen their connection. By removing should and eliminating negative judgment, we have successfully been able to transform our couples’ communication into meaningful dialogue and cultivate relationships that endure and thrive, allowing each individual to flourish in their authentic true selves.

Freeing ourselves from the panopticon of should is not merely about surviving the aftermath of trauma; it’s about thriving in the present. It involves acknowledging that experiences and traumas do not have to dictate our expectations or identities. When we allow should to shape our behavior, we risk losing authenticity in our relationships.

By reframing our language, taking personal responsibility, and creating greater resilience, we can develop more fulfilling interactions with our partners, embracing our true selves while engaging in meaningful conversations that heal rather than harm. This compassionate dialogue enables individuals and couples to break free from the invisible barriers of trauma, guilt, and shame, emerging stronger and more connected.

The journey toward authenticity and emotional intimacy is about recognizing that our feelings and needs are valid, independent of societal pressures or previous traumas. By practicing responsible language and showing vulnerability, we create an environment conducive to healing and shared growth. This process requires significant empathy and effort, allowing each partner to learn, grow, and genuinely support one another.

In conclusion, liberating ourselves from the panopticon of should means confronting and dismantling the negative emotions tied to rigid expectations. Trauma can challenge our emotional frameworks, and an overreliance on should only intensify our struggles. Recognizing that feelings of stress, guilt, fear, and paranoia often stem from conforming to unattainable expectations is a vital step toward healing. By embracing the complexity of our feelings without the weight of should, we foster authentic emotional connections and growth, allowing both individuals and couples to navigate the waves of trauma together. This understanding, although challenging, paves the way for a more open, authentic, and compassionate journey toward healing, intimacy, and love.

Take the Next Step

Contact us to learn more about our services and how we can support you on your journey toward greater emotional intimacy and fulfillment by learning about the impact of trauma on ourselves and our intimate relationships.

References:

Foucault, Michel. 1977. Discipline and Punishment. London: Tavistock.

Foucault, Michel. 1977. Discipline and Punishment: The Birth of the Prison. Trans. Alan Sheridan. New York: Vintage Books.

Foucault, Michel. 1980. Power/Knowledge: Selected Interviews and Other Writings, 1972-1977. Trans. Colin Gordon et al. New York: Pantheon.

Mason, M. K. (2024) https://www.moyak.com/papers/michel-foucault-power.html. Download 10/16/2024 at 4:20pm.

Cousins, N. (1979). Anatomy of an Illness as Perceived by the Patient: Reflections on Healing and Regeneration. New York : Norton.

Siegel, D.J. (1999). The developing mind: How relationships and the brain interact to shape who we are. The Guiford Press. N.Y., N.Y.